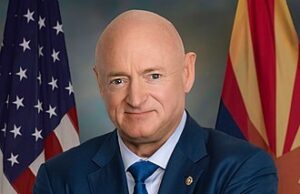

‘A hidden threat’: San Mateo lawmaker warns of rising groundwater risks, seeks study funding

Originally published on July 30, 2025 by the Mercury News and written by Ryan Macasero

WASHINGTON, D.C. – RealEstateRama – A Bay Area lawmaker is pushing for new federal legislation to study the threat rising groundwater poses — a hidden but growing environmental danger that experts say could worsen flooding, damage infrastructure, and contaminate drinking water.

U.S. Rep. Kevin Mullin, D-San Mateo, last month introduced the Groundwater Rise and Infrastructure Preparedness Act of 2025, a bipartisan bill co-authored with Rep. Andrew Garbarino, R-N.Y., that seeks $5 million in initial funding to assess the risks rising groundwater poses to public health and critical infrastructure like roads, utilities, and sewer systems. The measure would also support the development of long-term mitigation strategies.

Mullin held a press conference Tuesday morning in South San Francisco to discuss his new legislation and the region’s flood and groundwater rise threats with local environmental and government leaders.

“As we continue to witness the devastating and deadly impacts of flooding across America, we need to help communities understand their risks so they can better prepare,” Mullin said. “Too many lives, homes, businesses, and vital infrastructure have been upended by extreme flooding. Rising groundwater is a hidden threat that can remain unseen until it’s too late.”

The effort comes as the Bay Area has experienced more frequent atmospheric river storms and inches closer to sea level rise projections that experts warn will increasingly bring groundwater to the surface in low-lying areas. Mullin said his bill would fill a critical gap in understanding where groundwater rise will cause the most damage — and how to prepare for it.

Data is limited, but studies show the risks are significant. According to the bill, groundwater rise can mobilize toxic chemicals buried underground, increase the chance of chronic flooding, weaken the foundations of roads and buildings, and spread contamination to creeks and drinking water systems.

“Flooding won’t just damage communities in familiar ways,” Mullin said. “It will carry toxic contamination to places we never expected to find it.”

One of the most vulnerable regions is the Bay Area, home to thousands of contaminated sites, including former industrial zones and military bases. Among them is Bayview-Hunters Point, a former naval shipyard in San Francisco with a long history of environmental cleanup.

A 2024 report by the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) found that East Palo Alto, a historically disadvantaged and majority-minority community, is also at high risk of groundwater-related contamination due to its proximity to toxic sites and low elevation.

“In the Bay Area, there are over 5,000 toxic sites at risk of sea level and groundwater rise,” said Sarah Atkinson, SPUR’s senior policy manager for hazard resilience. “Rising water can cause contaminant mobilization into sewer systems and creeks. Community leaders are concerned about the resulting public health impacts and are demanding action — and this isn’t just a Bay Area problem.”

Mullin’s bill focuses on data gathering and planning for now, but he said it could lead to more substantial mitigation programs in the future.

“When I ran for Congress, I made it clear that I wanted to work in a bipartisan way,” Mullin said. “By focusing on the economic impacts, community impacts, infrastructure, and public health, I think we all know — everybody here knows — that climate change is real.”

Local flood resilience leaders say this kind of data is critical for smarter planning. Len Materman, CEO of One Shoreline, San Mateo County’s flood and sea level rise district, said cities and counties should be factoring in groundwater conditions when approving public and private construction projects.

“Local jurisdictions should require an analysis of the soil conditions that accounts for groundwater so that when projects are designed and then ultimately approved, they’re doing it thinking about future conditions — 20 or 30 years from now — with higher groundwater,” Materman said.

One Shoreline is urging local governments to require this type of soil analysis and long-term risk mapping before approving new housing or infrastructure projects.

The urgency has grown following a series of deadly floods in the United States. Earlier this month, extreme flooding in central Texas killed at least 136 people and caused widespread devastation. While the Bay Area doesn’t typically experience floods on that scale, Mullin warned the region isn’t immune.

“We’ve had very major rain events in the last four years, especially in San Mateo, where there have been deaths,” Materman said. “And it’s not to the scale of Texas, for sure, the loss of life. But certainly, the atmospheric rivers — the major storms that come through a few times a year or more — that’s having major impacts.”

Still, Mullin faces an uphill climb in getting the bill passed. Funding for climate resilience programs has faced repeated cuts in Congress. Under President Donald Trump, FEMA and NOAA budgets have been slashed as part of a broader push to reduce federal spending.

In May, another Peninsula lawmaker, Rep. Sam Liccardo, announced that $50 million in federal Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities funds had been cut, impacting coastal erosion mitigation efforts in Pacifica.

Mullin said the current climate in Congress makes it difficult to secure funding — but waiting isn’t an option.

“We may have a more friendly Congress in a couple of years, but we’re not waiting,” Mullin said. “We’re going to keep going on this because we can’t afford to wait.”

He emphasized that the risk groundwater rise poses affects the entire country.

“Rising groundwater doesn’t care if a state is red or blue,” Mullin said. “We are going to really focus on making communities more resilient.”